Once a quiet and underdeveloped corner of Haryana, the Nuh district has now gained national attention for all the wrong reasons. Previously known for its agrarian economy and developmental challenges, Nuh is emerging as a notorious hub of cybercrime. Much like Jamtara in Jharkhand, Nuh has seen a surge in digital frauds, phishing attacks, sextortion, fake job scams, and online identity thefts originating from its villages. What is particularly alarming is how this relatively underdeveloped district has evolved into an organized digital crime network, impacting victims across the country.^[1]

Nuh, part of the Mewat region, is economically and educationally backward with a literacy rate significantly below the national average.^[2] A combination of poverty, unemployment, and access to low-cost smartphones has created fertile ground for the growth of cybercrime.

Criminals rent out fields with good internet reception to make phishing calls and coordinate scams without disruption.^[3] The region’s proximity to Uttar Pradesh and Rajasthan allows scammers to escape easily and operate in cross-border criminal ecosystems.^[4]

Inspired by Jharkhand’s Jamtara scam network, small groups in Nuh operate phishing syndicates targeting citizens across India. The usual trick involves impersonating bank officials or customer service representatives and asking for OTPs, Aadhaar numbers, or KYC re-verification.^[5]

The accused often use forged documents to obtain fake SIM cards and open bank accounts. During raids, police recovered hundreds of Aadhaar cards, PAN cards, and ATM cards used to siphon off stolen money.^[6]

Criminals exploit weaknesses in the telecom sector. Telecom retailers often sell multiple SIM cards on a single identity proof without due verification. SIM cards were reportedly sold in bulk to scammers for ?1,200–?25,000 depending on the demand and legitimacy.^[7]

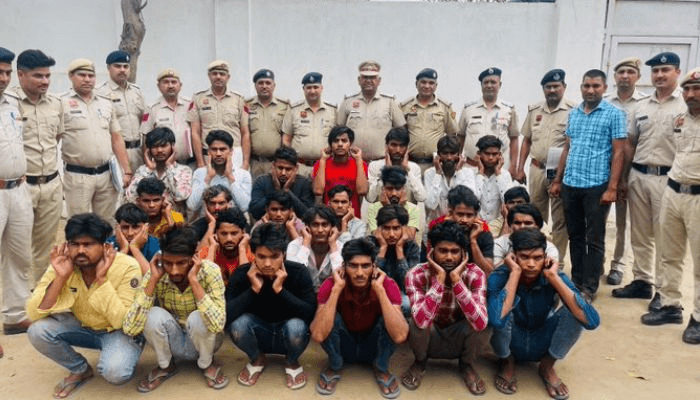

In April 2023, one of the largest cybercrime crackdowns in Indian history took place in Nuh. Over 5,000 police personnel conducted raids in 14 villages, arresting 125 accused and seizing digital and forged assets.^[8] Villages like Nai, Luhinga Kalan, and Jaimat were revealed to be operational bases for these scams.

In May 2023, the Haryana Police uncovered a ?100-crore fraud scheme affecting more than 28,000 victims across 35 states and union territories.^[9]

Another significant raid in January 2025 exposed a sextortion and fake taxi scam, where scammers posted misleading ads on social media and demanded money through blackmail.^[10]

Despite massive raids, systemic issues remain. Investigations reveal telecom operators and unverified distributors as major enablers of fraud. The local police have stated that fraudsters often use the same address for multiple SIMs, exploiting flaws in the Know Your Customer (KYC) norms.^[11]

The Cyber Police Station in Nuh was even attacked during the communal violence in July 2023, which was later confirmed as an attempt to destroy evidence and derail cybercrime investigations.^[12]

Some villagers, once engaged in cattle rearing or agriculture, now run restaurants and own property from earnings acquired through online scams. In interviews, several accused admitted they got into cybercrime for “easy money,” often guided by friends or relatives already in the racket.^[13]

Residents from neighboring areas like Gurgaon report regular scam calls originating from Nuh. Social media discussions reveal that locals are aware of the region's criminal repute but feel helpless against the scale of the operation.^[14]

India is witnessing a surge in cybercrimes. According to CERT-In, cybercrime incidents in India jumped from 208,456 in 2018 to over 1.4 million in 2021.^[15] The Centre launched the Indian Cyber Crime Coordination Centre (I4C) to consolidate response mechanisms, but its reach is yet to penetrate rural hubs like Nuh.^[16]

The situation in Nuh illustrates several key challenges:

Unless these core issues are addressed, the cybercrime syndicates are likely to regroup and re-emerge stronger.

To dismantle this criminal economy, a multi-pronged approach is necessary:

Nuh’s digital turn into a cybercrime epicenter exposes the vulnerabilities in India’s rapid digitization. It highlights the need for convergence between law enforcement, policy reform, education, and economic development. The police crackdowns have been effective in short-term disruption, but without systemic change, the deeper roots of the problem will persist.

What happens next in Nuh may well set the tone for how India addresses its growing cybercrime challenge in the years to come.

Ministry of Home Affairs, Indian Cyber Crime Coordination Centre (I4C), https://cybercrime.gov.in/.

N-55, Sri Niwas Puri, New Delhi 110065

ireneslegal9@gmail.com

+91 995 378 5058

Copyright © ireneslegal.com. All Rights Reserved.

Designed by Questend India Pvt Ltd